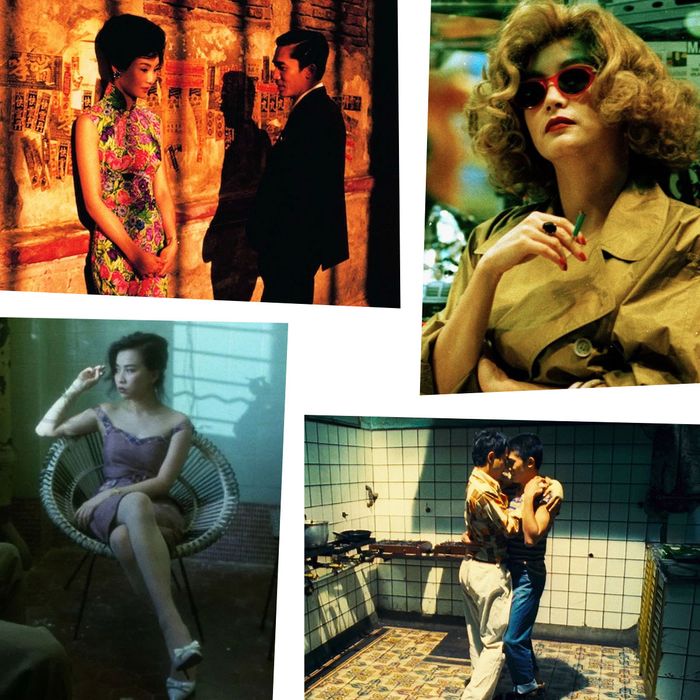

How do you make a mood? “At the high point of our intimacy, I was just 0.01 centimeters away from her,” is a line spoken in the Hong Kong film director Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express that offers some clues. In Chungking, people are forever missing each other by minutes or millimeters, and it is from the synaptic spaces between them that Wong Kar-wai conjures a sense of forlorn longing and could-have-been. You might want these schisms to close — for the well-matched strangers to consummate their flirtation, for the broken-up couple to reconcile — until it occurs to you that the resolution of plot points feels like a secondary concern. Wong Kar-wai is known for his auteur-ish depictions of life in 1960s Hong Kong; a handful of these are included in a new Criterion Collection box set. The director can make a study of a young Cantopop star languishing in the heat of late summer as an electric fan whirs nearby. Then, before you’re even aware it’s happening, by some magic, it’s there: a mood.

By Wong Kar-wai’s formulation, it takes at least two to make a mood. (One to preen, the other to watch.) This diagnosed my own teenage malaise — that of being Asian and alone — but offered no ready solution for me, marooned in a mostly white suburb of Maryland with my inarticulable feelings of racial difference. Beyond a dim self-loathing, I remember my teens by the reactions I provoked in other people, mostly white classmates: annoyance at my tendency toward over-earnestness, which made me uncool; confusion at my under-assertiveness, which made me unmemorable. At age 17, I watched In the Mood for Love, Wong Kar-wai’s 2000 film about a pair of jilted lovers who, having found one another, refuse to commit the same sin as their unfaithful spouses. I sat for a few long minutes afterward, feeling uncool and unmemorable and a little verklempt but also — a new sensation — vindicated. The marital discontents at the center of the film were unfamiliar to me, but I thought I could understand the weight of a secret sadness, borne alone by necessity. I read this burden in the bowed heads of both leads. Never, I thought, had sad looked so good and felt so relatable.

A Wong Kar-wai movie is stupid with small moods, is practically swimming in them, and succeeds by making the ugliest and most minute of its moods extremely beautiful. I flattered myself that I could see glimmers of me in Wong Kar-wai’s characters, particularly in their tendency to leave certain home truths unspoken, often to their own detriment. Dialogue is spare, in general; gestures and objects form the expressive units of a different sort of vernacular. In Chungking Express, a cop alone in his cramped apartment speaks to a bar of soap and a dishrag like old friends; elsewhere, another cop marks the days until May 1st (his ex-girlfriend’s name is May) by buying tins of sliced pineapple set to expire on that day. Happy Together, my favorite of Wong’s movies, follows a queer couple, played by longtime Wong collaborators Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung, who decide to start over in Argentina. They break up, tango in a seedy kitchen (not a euphemism), and bum cigarettes on street corners in the La Boca neighborhood of Buenos Aires. In Days of Being Wild, Leslie Cheung is an aimless playboy who initiates a relationship with a concessions-stand worker, played by Maggie Cheung. He soon leaves her for Carina Lau’s spirited cabaret dancer, who enters his apartment and lays claim to everything contained within, including Leslie Cheung.

In each of these, I could detect the odd interplay of the non-verbal and the stubbornly material that characterized the language of my home life. My first thought, on watching Chungking, was of my dad’s habit of overbuying foods that he knew I liked. Once, I made the mistake of telling him that I liked blueberries and came home to find that he had stocked the refrigerator with six pint-size containers of them. “Not a substitute for real food,” he warned me. Still, in subsequent days, I ate handfuls of blueberries until my stomach hurt. I was paranoid that soft rot would consume the fruit before I did. We might have spared each other both cost and stomachache if he had told me that he intended to buy out the grocery store’s stock of blueberries and I had told him to stop, but we didn’t, of course: That wasn’t how the Xiaos operated.

In Happy Together, Leslie Cheung returns to Tony’s apartment with three crumpled packs of cigarettes as a kind of peace offering after another lover’s quarrel. Later, Tony buys cartons of them — an embarrassment of cigarettes, enough to cover a tabletop — to keep Leslie from wandering the streets of La Boca late at night. Leslie is finely aware of the mechanism of Tony’s attempted control; in a silent rage, he sweeps the boxes of Le Mans from their place on the shelf where Tony has stacked them like bricks. The lopsidedness of their relationship is laid bare by this display. Goods, at best a means for expressing affection that otherwise has no outlet, are warped into something like currency, and Leslie, alas, cannot be bought. Forget the cigarettes, I wanted to scream at Leslie. Tell Tony you’ve been a piece of shit, tell him you love him. He never does.

Across the Pacific, in the universe of Days of Being Wild, when Maggie Cheung realizes that Leslie (the same Leslie Cheung, as a different scoundrel) has left her for good, she confesses to Andy Lau, the cop patrolling the quiet street below Leslie’s apartment, that she’s resorted to burying herself in her work in order to forget about the boy. She forges a friendship with Lau, an unlikely interlocutor. They are both pining after different people, their desires at cross-purposes, so their alliance remains platonic. The slow-unfolding beauty — and agony — of Days of Being Wild is owed in part to these misalignments of time and intention, which are rarely perfectly-matched in real life anyway.

Such are the logistics of a Wong Kar-wai movie — people bear each other’s crosses without complaint or are crushed under crosses of their own making. Selfless acts, spurned by their intended recipients, are revealed to be self-indulgent in an ironic twist. So much is imputed into the exchange of goods and gifts, in the offering of a cigarette or a light. Small power plays and demonstrations of affection that could be tendered in a few words are drawn out here in gestures and props. It is all useful in creating a mood — one familiar to me in its suggestion that, if people were more frank, they might spare each other a whole lot of miscommunication and heartbreak, at the high cost of nuance and realism.

Despite their palettes of otherworldly reds and greens, Wong’s movies are characterized by an appreciation for unvarnished detail that borders on vérité. This seeds a tempting proposition, especially for second-gen kids who stumble upon his work. I confirmed this recently during a conversation with Vanessa Li and Bowen Goh, the 28- and 30-year-old owners of a bar in Bushwick called Mood Ring; its name is a nod to In the Mood for Love. We were talking about our parents’ and grandparents’ preference for television dramas and movies with uncomplicated plotlines whose resolutions, like those of fairy tales, leave nothing to be desired — an opposite sensibility to a Wong Kar-wai production. Goh said that Wong’s films provide a unique kind of visual stimulus, its objects just familiar enough to elicit an easy empathy from him. Li agreed — her family is from Hong Kong, she told me, and shots of the city’s crowded alleyways hold a special significance for her. Goh mused that the Hong Kong of Wong’s films was relatable enough that he could imagine what life for his parents, who are from Guangzhou, might’ve been like, or — after a beat — “what it could’ve been like for me.”

Perhaps the older generations have it right, and the best kind of escapism conjures worlds so far beyond reach that they don’t inspire rue, only fancy. I know that, for a few hours after my first viewing of In the Mood for Love, I tried to imagine my life as a Wong Kar-wai production: all atmospheric everything, with the handful of Chinese women I knew transposed into chatty, cheongsam-wearing aunties. We could be free to slink around our city — a real, heaving metropolis with monsoon rains in late June — feeling fundamentally alone. We would gather in smoky kitchens after dinner to play mahjong and drink rice wine, and communicate by an infinitude of small gestures, all of them mutually understood: inclinations of the head, lifts of a brow. Our ugliest moods would still look pretty, and our prettiest moods would look sublime.

"film" - Google News

April 30, 2021 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/3t88gPW

Recognizing My Asian Heritage on Film - The Cut

"film" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2qM7hdT

https://ift.tt/3fb7bBl

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Recognizing My Asian Heritage on Film - The Cut"

Post a Comment