Every so often, a strange alchemy leads to a particular year producing a disproportionate amount of cultural gold. Such was the case, 50 years ago, in 1971. In music, those 12 months gave birth to a mind-boggling array of instant classics across rock 'n' roll, reggae, soul, and beyond – records that included Marvin Gaye's What's Going On, Paul McCartney's Ram, and Joni Mitchell’s Blue, among countless others. In the movies, meanwhile, 1971's legacy was an unforgettable mosaic of images in game-changing works: the sort of worldwide creative output that few could turn their eyes from, whether it pleased or offended them.

More like this:

– An epic about the turmoil of 70s America

– A cynical masterpiece about fake news

– The romance that broke several taboos

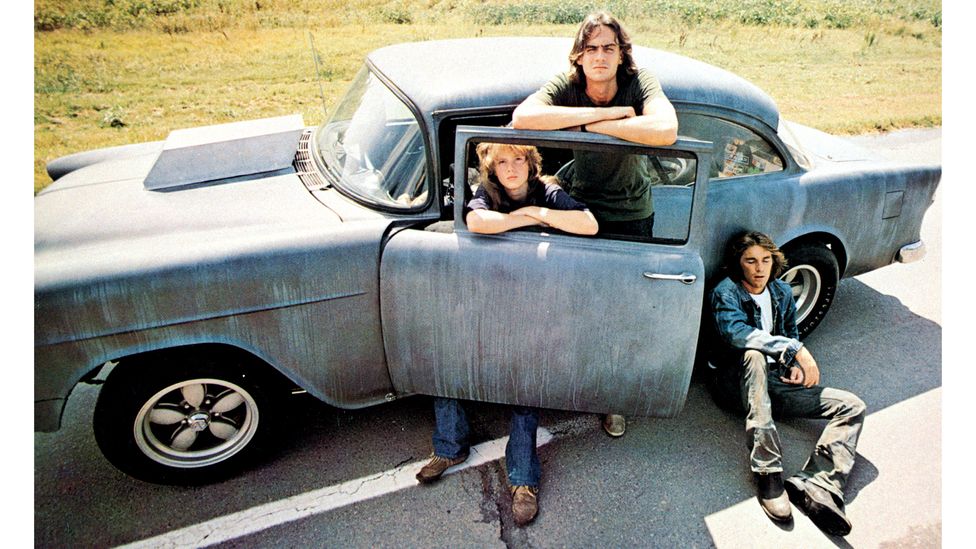

1971 gave us, among other things, A Clockwork Orange, Stanley Kubrick's shocking descent into dystopian cruelty; Get Carter, the British crime film, whose murky fatalism offered an antithesis to the cheerful escapism of the swinging sixties; Dirty Harry, in which Clint Eastwood's squinting, gravel-voiced cop announced a return to cowboy justice against hippie "punks"; and Two-Lane Blacktop, the minor-key masterpiece of US road movies, with its disaffected, drifting youth, sun-browned and scruffy-haired, melancholy against the roar of their Hemi engines.

Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange was among a wave of provocative, maverick films that came out in 1971 (Credit: Alamy)

And that's not even scratching the surface: in British and American cinema alone, there was artwork as varied and accomplished as Shaft, McCabe and Mrs Miller and The French Connection; Harold and Maude, The Last Picture Show and The Devils; Sunday, Bloody, Sunday, Klute and Vanishing Point.

And 1971 was also situated bang in the middle of several remarkable movements: American blaxploitation, Italian crime movies, and Bollywood cinema, among others. It was the year that gave us works from masters like Robert Bresson (Four Nights of a Dreamer) and Nicolas Roeg (Walkabout), and directorial debuts from Elaine May (A New Leaf) and Clint Eastwood (Play Misty for Me).

The beginning of an uncertain age

Why was it such a special year? Well, 1971 stood at the precipice of a wild decade – described as one in which movies actually mattered by film historian David Thomson. In terms of Hollywood filmmaking, the first spectacle-driven, market-orientated blockbusters (like Star Wars and Jaws) had not yet arrived on the scene. By the late 1960s, the industry was floundering financially, and many of the struggling major studios were bought out by non-media companies, famously Gulf & Western oil company in the case of Paramount. By '71, film production in Hollywood had slowed to a trickle, and cinema admissions were less than a quarter than what they had been during their heyday in the 1940s. There was no set path for studios to follow, and no certain road into the future of filmmaking.

When critics and scholars talk about the remarkable artistic flowering that came from the "New Hollywood" of the '70s, they often talk about how artists slipped through the cracks in the chaos between the old guard fading away and the new guard taking over. By 1971, this seemed to be precisely what was occurring.

Partly because of their desire to make films that pandered to the youth market, and partly because of a genuine inability to come up with a reliable barometer of box office success, studio heads gave unprecedented freedom to younger writers and directors to lead the way. This blooming movement saw independently-minded filmmakers and artists shattering the forms and paradigms of traditional film style, and along with it the censorious rules of the past vis-a-vis sex, politics, and violence. It resulted in a whole decade of remarkable filmmaking, and it's in the films of 1971, where this new age was at its freshest, that the transfer of power can be felt most exhilaratingly.

Alan J Pakula's Klute, starring Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, reflected the rise of second-wave feminism (Credit: Alamy)

The phenomenal richness of the creative output in 1971 and beyond was not just about the material circumstances of the industry, but the profoundly unsettled era that filmmakers were responding to. In the US, there was a distinct hangover from both the political assassinations of the '60s (John F and Bobby Kennedy. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X) and the continuation of the Vietnam war; the mental anguish of exploding skulls and napalmed children on the evening news; the outrages of the My Lai massacre and unpunished war criminals in the US military. The entire edifice of faith and optimism in national life had begun to crumble. In Britain, there was rebellion against the droning conformity and classism of a nation still hanging onto pre-war values; mounting, regular sectarian violence in Northern Ireland; and the rise of the National Front.

For a good sense of what the collective mood may have been then, it's worth watching the new Apple+ series 1971: The Year that Music Changed Everything, produced by Oscar-winning documentarian Asif Kapadia, which contains a great deal of compelling archival footage from the time. Over the course of eight episodes, it explores in great detail the socio-political backdrop that informed the artists of the time, whether it be the Attica prison riots, Black radicalism from Los Angeles to London, or the plight of suburban housewives grappling with second-wave feminism. Similarly, movies – from Shaft to Klute – were touching on the very same subjects.

Of course, progressive though so much in '71 was, the backlash against those movements were also building up steam, and that was apparent in cinema, as in wider society. Amid US films, there was often a fascinating split: on the one hand you had pro-establishment works like Dirty Harry, which would quietly reinforce cops as heroes… and on the other those like Vanishing Point, with an anti-heroic speed freak on the run from the law, which embraced the spirit of the counterculture and sought to expose the powers that be.

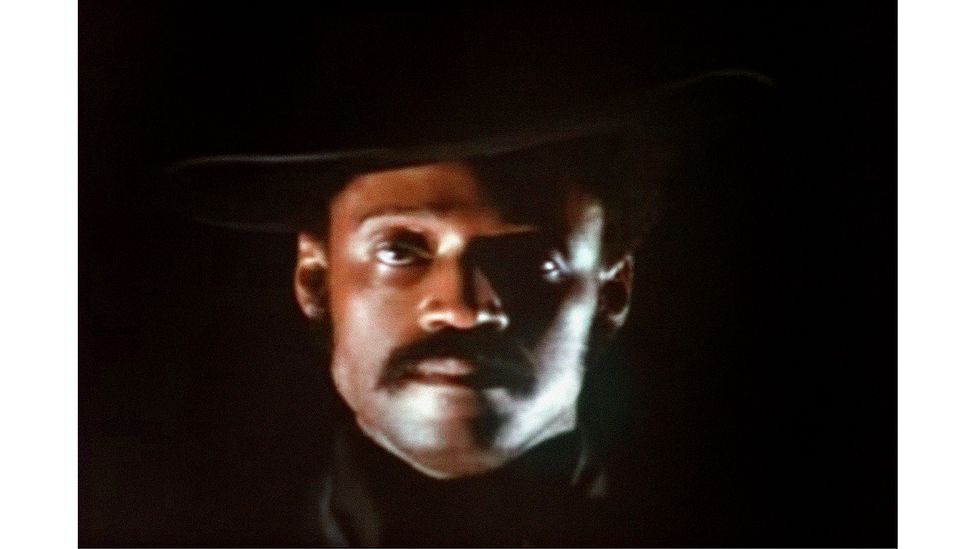

Understandably, many filmmakers of the year had the tendency to wear their political leanings on their sleeves. Films like Dirty Harry would use the Manson murders as an excuse to paint youth movements as dirty and psychotic, requiring a blunt application of police force. Meanwhile cops were painted as a force of oppressive white supremacist power in Melvin van Peebles' landmark Blaxploitation film Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song ("This film is dedicated to all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the Man", it proclaims.) It probably helped Sweet Sweetback that it was an entirely independent venture, with no limit on its polemical worldview.

Another truly independent film from that year embodies a dissenting vision better than nearly all others: Punishment Park, from the maverick British filmmaker Peter Watkins, which casts a caustic observational eye on an America convulsed with violence and civil unrest and imagines an alternate reality of the nation turned into a right-wing police state. Punishment Parkis a pseudo-documentary, in which a British film crew follow a selection of government-detained US anti-war protestors, Black Panthers, and feminists placed in internment camps for their risk of "insurrection". There, in a cruel cat-and-mouse game, they are given an opportunity to try to escape – but if they don’t make it, armed police will mow them down.

Melvin van Peebles' landmark Blaxploitation film Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song painted cops as a force of white supremacist power (Credit: Alamy)

Shot down-and-dirty in 16mm, cinema verite-style in August 1970, amid the blazing desert heat of Southern California, it is a profoundly pessimistic film which punctures the image of law and order and good government. By the time of its release in 1971, it proved almost eerily prophetic: by then, a targeted break-in had revealed the FBI's Cointelpro program, which showed the extent to which government moles had gone to terrifying lengths to divide and conquer activists. Watkins' satire contends that healthy dissent was being suppressed in the US, and given that the film was only released in one New York cinema, from which it was then mysteriously pulled after only four days, this seems to have only proved his point.

Then v now

However, if looking back at the films of 1971 offers the chance to revel in a superlative cultural moment, perhaps it also places the state of cinema today in sharp relief. Fifty years later, societal tumult has not disappeared, though it has altered. We have been brought low by a virus that has only deepened and drawn attention to fault-lines of inequality across race, class, and nation. On matters from racism to climate change, people remain at serious odds. The division baked into cinema back then is as rife as it ever was, but are the movies as good as they once were?

Arguably, not. Half-a-century later, US cinema has never felt more constrained by prevailing market forces, and its lack of original material has never seemed so obvious. As a filmmaker who came up in the 1970s, Martin Scorsese seems to feel strongly about the shift in Hollywood from then to now, and in a controversial New York Times op-ed in November 2019, he explained why, pointing to the idea artists seem more beholden to the dictates of gargantuan streamers and media giants than ever, making films that "satisfy a specific set of demands, and are designed as variations on a finite number of themes".

Meanwhile what, in 1971, felt like a rich current of discourse around cinema as art, often exemplified by debates held on major TV programmes such as America's Dick Cavett Show, and in national newspapers, has been sidelined. On social media, measured debate is often drowned out by fan culture, where people attack dissenting critics of their favourite superhero products, such as the work of Zack Snyder. "I think the biggest difference between then and now is that movies then made demands on the audience – and the audience was there to meet the challenge," says Thomas Doherty, cultural historian and professor of American Studies at Brandeis University. "The symbiotic relationship gave the directors such confidence knowing that moviegoers were willing to take a flyer on a bizarre, provocative, revisionist, off-putting film. Don't like unhappy endings? Too bad. Can't tell the good guys from the bad guys? Grow up."

To be sure, cinema has also moved forward for the better in many ways. Another 1971 release, Sam Peckinpah's chilling home invasion thriller Straw Dogs, contains one of the most appalling rape scenes in the history of cinema, which implies that the female character who is the victim enjoys the assault. The fact also remains that many of the "canon" films from '71 are Anglo-American, and focused inward on problems of their own countries even as these countries were imposing their force elsewhere. Vietnamese filmmakers like Hải Ninh, for example, documented the war that ravaged their nation but many of the films are still difficult to see with English subtitles. And the industry was still centrally the dominion of the straight white man, despite the challenges made to their authority by a series of directors like Ossie Davis, Gordon Parks, Melvin van Peebles, and others. Today, by contrast, the perspectives of a variety of once-marginalised groups are being brought to the fore, and representation is being centred in discussions about filmmaking, like never before.

Monte Hellman's road movie Two-Lane Blacktop cast aside traditional narrative for a poetic, often wordless journey (Credit: Alamy)

Yet diversity is not the only barometer of a film's ability to engage with social and political issues; if a film is nullified of all individual artistic imprints or provocative thinking – as, it could be argued, the endless stream of entries into modern blockbuster franchises have been – it hardly matters who's doing the acting or directing. "So many films today don't ask much of the audience. They are in the satisfaction business," says Doherty. Of course, not everyone agrees. Some have critiqued the opinions of those such as Scorsese as elitist, or as Boston Globe columnist Jeneé Osterheldt put it, "an attack of the fantastical imagination and a recurring hammer dropped by the gatekeepers in the world of so-called fine arts". And to be sure, there are exceptions (that mostly prove the rule): several Academy Award-nominated films in the past few years were made by an excellent crop of singular directors including Barry Jenkins, Chloe Zhao, Lee Isaac Chung, and others. But regardless of what you think of today's cinema landscape, one thing is clear: things have changed drastically.

Take Two-Lane Blacktop, Monte Hellman's cult road movie from 1971. Two aimless young men (known only as "the driver" and "the mechanic", and respectively played by musicians James Taylor and Dennis Wilson) cruise along US highways in their souped-up old car, challenging others to drag races for cash. They pick up a teenage girl (Laurie Bird) who's hitchhiking along the way and form their own little long-haired family, as they enter into a cross-country race with a bourgeois stranger (Warren Oates) in a fancy new GTO. But the race never exactly finishes; they often get off-track, or one stalls and needs the others' help, which they offer each other with curious magnanimity. This poetic, often wordless journey becomes a strange little feedback loop, casting aside traditional narrative ideas of ambition and drive and instead celebrating the courage to be lost. Imagine characters and stories in Hollywood cinema in 2021 able to be meaningfully lost, cast into ambiguity, like the quiet protagonists of Two-Lane Blacktop. Imagine what Hollywood might rediscover within itself if it had the same courage.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"film" - Google News

June 17, 2021 at 06:02AM

https://ift.tt/35smP7B

Why 1971 was an extraordinary year in film - BBC News

"film" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2qM7hdT

https://ift.tt/3fb7bBl

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why 1971 was an extraordinary year in film - BBC News"

Post a Comment