The late film director Ken Russell was the embodiment of outrageous cinema. From his early documentaries and biopics about famous composers for the BBC to feature films such as Women in Love (1969), The Music Lovers (1971) and Tommy (1975), Russell became one of Britain's most unique screen artists.

More like this:

– The history of 'shock' cinema

– The most outrageous film ever made?

Today, one film of his above all others is still considered controversial: 1971's The Devils. Based on real events that occurred in a 17th-Century French town, it caused more than a few sleepless nights for the censors.

The Devils centres on 17th Century French priest Father Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), who was accused of possessing nuns in the town of Loudun (Credit: Alamy)

The Devils follows the fate of Loudun, a self-governing town under the temporary protection of the debonair, womanising priest Father Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed). Cardinal Richelieu (Christopher Logue) plots with King Louis XIII (Graham Armitage) to take control, but their men, led by Baron De Laubardemont (Dudley Sutton), face strong opposition from Grandier.

However, the obsessive lust for Grandier held by the town's abbess Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave) leads to the nun making a false accusation that he has possessed her, which the establishment exploit in order to oust him. Hysteria then unfolds among Loudun's Ursuline nuns, leading to a mass orgy, a chaos for which Grandier is blamed. Charged with heresy and cavorting with devils, he undergoes a show trial which will only ever go one way.

Russell became aware of the filmic potential of the story of the so-called "Loudon Possessions" through a 1960 play by John Whiting based on the same historical events. "He first saw it when it was on the London stage," Russell's partner Lisi Tribble Russell tells BBC Culture. "It inspired him to immediately research the text that the play was based on: Aldous Huxley's [novel] The Devils of Loudun." Impressed with Huxley's detailed interpretation, Russell started work on his script. Writing to the soundtrack of Krzysztof Penderecki's opera, based on the same events (as well as Sergei Prokofiev's The Fiery Angel, another work about religious hysteria) he adapted the story with equally fiery aplomb.

Fifty years on from its release, The Devils is a film rightly celebrated for its artistry. Its startling array of performances, in particular Reed and Redgrave's, are some of the best British cinema has to offer. The film's score by British composer Peter Maxwell Davies is unique and haunting, and especially great considering it was his first. The visual style of the film is also stunning, in particular the sets designed by a young Derek Jarman, inspired by the Huxley line about Sister Jeanne's exorcism being akin to a "rape in a public lavatory". The Devils is a white-walled nightmare of a film with a horrifying wipe-clean aesthetic.

Yet it was the theological, political and sexual content that landed Russell in hot water. The film's mixture of demented sexuality, raw violence and religious imagery was a heady mix, even by Russell's standards. Scenes of torture and death linger long after viewing, as does the pervading nihilistic atmosphere. Sex and death become so intertwined with the film's theological imagery that they feel inseparable by the end. And this is before considering the film's portrayal of the allegiance between the state and the church in achieving their violent, greedy aims. Fifty years on, the film still shocks, such that the Warner Bros studio has never released the full director's cut.

Even in its censored state, the London Evening Standard critic Alexander Walker famously decried the film, as looking like the "masturbatory fantasies of a Roman Catholic Schoolboy." Such was the vitriol of Walker's review that he ended up on the BBC alongside Russell to discuss the film, only for the director to roll up a copy of Walker's own review and hit him over the head with it.

One of the film's most stunning elements is the nightmarish white-walled sets designed by a young Derek Jarman (Credit: Alamy)

As in the UK, The Devils was panned in the US. Roger Ebert wrote one of his most sarcastic reviews, giving the film zero stars. "Ken Russell has really done it this time", he sneered. Pauline Kael, another critic of Russell's work, was equally scathing in the New Yorker. Lisi remembers Russell's reaction. "He was stoic (with effort) in accepting that the critics attacked it, but reminders of certain reviews would make him bitterly wince for the rest of his life."

A profound political statement

Russell's frustration is understandable. Beyond the controversy, the film is a profound piece of work. The Devils is about many things but is chiefly a critique of power. Russell described the film as a conscious political statement. Its political zeal is also what saved it from an outright ban, the censors in the UK at least recognising the creative and intellectual aspects of the film. Darren Arnold, author of the monograph Devil's Advocate: The Devils, agrees that it is a work of real intellectual value. "Russell liked a bit of mischief and wasn't afraid to push a few buttons," he tells BBC Culture, "but, amidst the mayhem, The Devils contains a powerful and sincere message." The message is that outrage and heresy can be easily weaponised by the powerful. The film, however, ironically became a meta-comment on its own hysterical treatment as a blasphemous piece of work.

The threat of violence towards any who disagree with the state authorities leads to many characters' collusion, pretending Grandier deserves his subsequent torture and public execution. It is a story of the gullible descending into a mob. "You have seduced the people in order to destroy them," shouts Grandier to the court when facing his charges. Truth is a scarce commodity in times of strife.

As the film shows, death was already normalised in the town at the time of these events: Loudun was weakened by plague, inoculating people to the suffering of others. "There was death in the air, death, decadence and destruction," as Russell suggested in a 2012 DVD commentary on the film. It laid the way for a more organised political violence.

Grandier's biggest mistake is to admit his imperfections, especially regarding his marriage to Madeleine (Gemma Jones). In breaking his vows of chastity, such an act of undiluted love is deemed just as blasphemous as the admittance of simpler carnalities. Flaws are utilised by those who cynically claim evangelical purity. The braying mob merely strengthens as he admits his human fallacy. Only an ultimate act of destruction will satiate their mania. It is a theme which feels depressingly timeless, from the countless historical scandals generated by art and culture in centuries gone by, to modern-day, social media-driven outrage.

Another factor to consider in the narrative is sexual repression. Sister Jeanne's lust deranges her to such an extent that her playacting at possession may as well be genuine. Her desire is distorted into a destructive power. She responds easily to the lies she is fed, in particular those of Father Barre (Michael Gothard), a proto-hippy shaman deployed by Laubardemont to exorcise the nuns. He gains his own pleasure from the spread of deranged untruths and is a dark cipher of the hang-ups from the period of the film's production; a predatory cult leader akin to Charles Manson or Jim Jones.

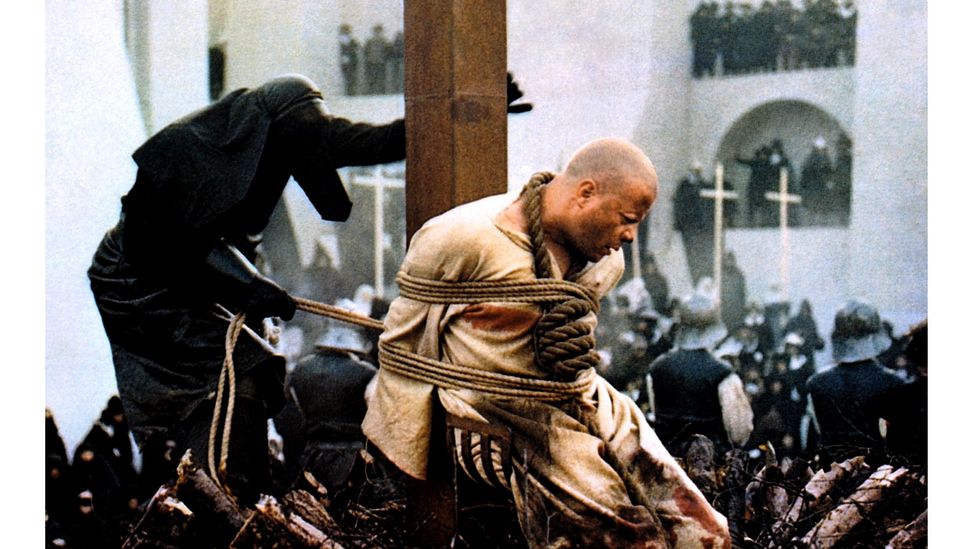

The momentum of violence grows beyond the control of those who stoked it. In the climactic scene, having been found guilty, Grandier is put on a pyre and refuses to confess his decreed sins to Father Mignon (Murray Melvin), in spite of the merciless destruction of his body. The virtue of the establishment figures, professing a desire to save his soul, collapses with the walls of the city which are destroyed on Laubardemont's orders. As we, the audience, knew, Grandier's damnation was all a ruse to destroy Loudun's independence. Malice succeeds by veiling itself in piety and social sanctity. Only ruins are left, as the film's stunning final shot shows, with Madeleine stumbling through the debris of what little remains.

Father Barre (Michael Gothard), a shaman deployed to exorcise the nuns, bears a resemblance to the predatory cult leaders at the time of the film's production (Credit: Alamy)

The ultimate testament to The Devils' power is the fact that Russell and his collaborators were to face an equally gruelling inquisition that exemplified exactly what the film was trying to explore. In telling Grandier's story, Russell caused as sensational a furore as the priest did with his defiance.

Indeed, throughout the editing of The Devils, a strange parallel grew between Grandier and Russell. It seemed that their heresy became one and only their final paths differed. Where Grandier's body was the required sacrifice to appease the outraged on screen, Russell's control of the film was the victim.

The censorship nightmare

Even before The Devils found its way onto screens, its various edits were already raising concerns. Russell had an array of people to satisfy and editing it was a huge and tortuous undertaking considering the button-pushing nature of his filmmaking. The director had to keep the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) and the American producers at Warner Bros content. It would be an impossible task.

Russell found an unlikely ally in John Trevelyan, the outgoing secretary of the BBFC. Along with the BBFC president, Lord Harlech, Trevelyan was shown rough edits at Russell's request in the hope of it being passed with their amendments. Though uncertain about several of the film's more extreme segments, Trevelyan saw the earnest aims of Russell's project. "Thankfully Russell's sincerity wasn't lost on Harlech and Trevelyan – else we may not have seen the film at all," says Arnold.

Russell reluctantly agreed to their suggested cuts in order to achieve the X certificate for British distribution. This made the film just possible to release in the censorious climate in the UK at the time, created in part by evangelical groups such as Mary Whitehouse's National Viewers' and Listeners' Association. Whitehouse had already caused Russell trouble around his BBC play Dance of the Seven Veils (1970) which was subsequently banned for its satirical portrayal of Richard Strauss' association with Nazism, thanks also to pressure put on BBC by the composer's estate.

Another of Whitehouse's projects, the anti-permissive group The Festival of Light, quickly objected to the passing of The Devils by the BBFC and protested its screenings, organising an effective letter writing campaign to the new chief censor Stephen Murphy who had taken over from Trevelyan. The campaign succeeded, with several local authorities banning screenings in spite of the BBFC’s approved rating. "The thing I thought about The Devils is that, at the higher quality it was, the worse the blasphemy could have been," Whitehouse suggested in the 1995 documentary Empire of the Censors, "High quality doesn’t excuse blasphemy. Blasphemy is blasphemy full stop."

The Motion Picture Association of America cut further still for its US release. The 111 minute British cut became the 108 minute US cut, in particular removing any imagery showing pubic hair. Such was the severity of the editing that Russell called the US release "disjointed and incomprehensible". The cuts were haphazard and in particular broke the tempo of the film's orgiastic centrepiece, the crescendo of heresy falling flat. "He was devastated by America's decision to release a butchered version of the film," Lisi recalls. "He felt their truncated version heightened the hysteria and destroyed much of the essential rhythm of the film."

In the climactic scene, Grandier is put on a pyre and burnt to death as the final step in the King's ruse to destroy Loudun's independence (Credit: Alamy)

One scene that escaped neither British nor American intervention is the "Rape of Christ" sequence, the finale to the orgy, which sees a large statue of Christ assaulted by a variety of rampaging naked nuns. On top of that, a sequence in which Sister Jeanne masturbates with the charred femur of Grandier after his death was also removed in both US and UK versions.

It was thanks to critic Mark Kermode, along with director Paul Joyce, that these two scenes, thought to be missing, were unearthed from an archive and reinstated by the film's original editor Michael Bradsell. However, in spite of renewed pressure for this full director's cut to be released, it remains unavailable. That's despite the fact that when members of the BBFC attended a special screening of the cut in 2002, they had no issue with the reinstated scenes. Various petitions for Warner Bros to release it are ongoing. According to Kermode, in a 2014 episode of his video blog Kermode Uncut, their last response suggested the film's "distasteful tonality" to be the barrier to its future re-release. Instead, audiences have to make do with the truncated versions: in the UK, the British cut can be viewed thanks to the 2012 BFI DVD release, while in the US, the 108 minute cut Russell was so unhappy with is available to stream on iTunes America.

Despite its mistreatment by Warner Bros and, over the years, being difficult to access, The Devils continues to endure in the cinematic canon. This is largely thanks to the passion of its fans, from critics such as Kermode to filmmakers such as Alex Cox and Oscar-winner Guillermo del Toro. In 2014, del Toro called the continued treatment of the film a "true act of censorship."

"Ken made his peace with it," Lisi concludes. "I imagine that from his greater vantage point in the cosmos, he undoubtedly hopes against hope that it will someday be declared acceptable as a significant contribution to world cinema and an example of his, Reed's and Redgrave's unique insight, talents and bravura." The only real outrage today regarding Ken Russell's The Devils is that this unparalleled British masterpiece is still unavailable to see as its director intended, even 50 years on.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"film" - Google News

August 03, 2021 at 06:02AM

https://ift.tt/3fkYOVq

Why X-rated masterpiece The Devils is still being censored - BBC News

"film" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2qM7hdT

https://ift.tt/3fb7bBl

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why X-rated masterpiece The Devils is still being censored - BBC News"

Post a Comment