There are uncanny parallels between this year's Tokyo Olympic Games and those held in the same city in 1964. Each tournament was disrupted by a global crisis: the first Tokyo Games, due to take place in 1940, were cancelled after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, with global conflicts effectively costing the nation an opportunity to host for another 24 years; the second Games were pushed back a year in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Each event has presented an opportunity to showcase the rejuvenation of a country decimated by a nuclear catastrophe. Little Boy and Fat Man were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, while the earthquake-provoked Fukushima disaster in 2011 was the worst of its type since Chernobyl.

More like this:

- How Riefenstahl shaped the way we view the Olympics

- The film that changed how we see sport

- The book that changed Japan's image

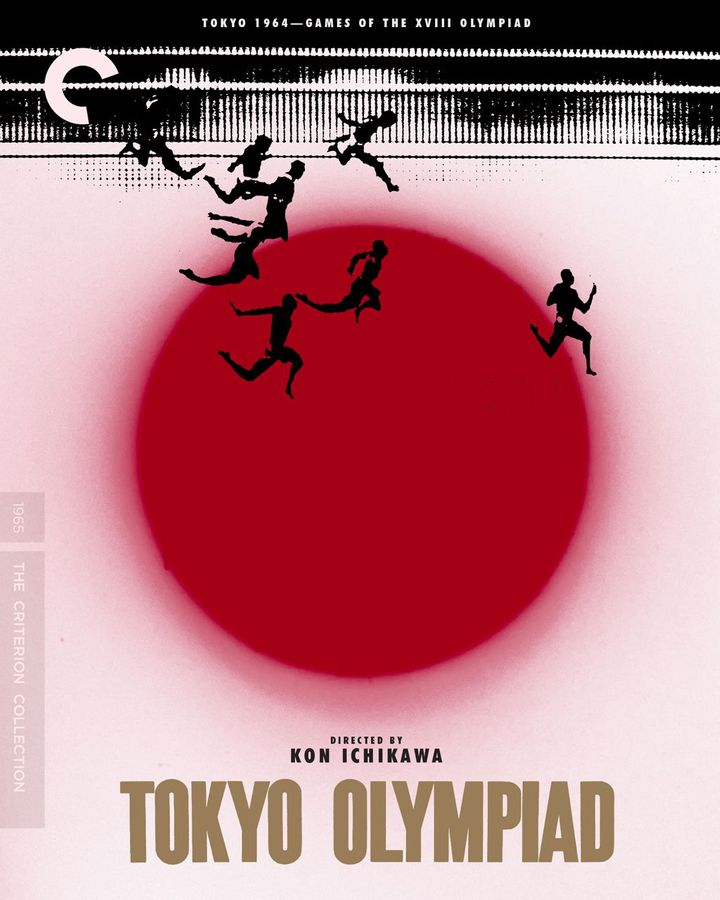

In the wake of these disasters, the official Olympics film (a tradition of more than 100 years, commissioned by the International Olympics Committee for reasons of posterity) would be vital in projecting a new vision of the nation to the world. In both 1964 and 2020, the task fell to a director already in part responsible for restoring Japan's global cinematic reputation. Kon Ichikawa, director of the 1964 Olympics film Tokyo Olympiad, had been a key figure of Japan's "Golden Age" of cinema in the 1950s, and had been recognised at the Cannes and Venice film festivals. The 2020 Games' documentarian Naomi Kawase became, in 1997, the world's youngest recipient of Cannes' Camera d'Or prize for directors – and the first-ever female Japanese recipient. [That year both the Palme d'Or and Venice's Golden Lion were also awarded to Japanese directors in a coup for the nation's film industry.]

The sublime Tokyo Olympiad (released in 1965) won Ichikawa two Baftas and the Olympic Diploma of Merit. It is a film that artfully communicates much about the significance of the Olympics for a country in transition, which was banned from competing at the 1948 post-World War Two Games in London. But although she "very much empathises" with Ichikawa's approach, Naomi Kawase tells BBC Culture via an interpreter, the circumstances under which she finds herself taking on his former role – 57 years later – are starkly different. Kawase's film will capture a host city that has just re-entered a state of emergency, whereas Ichikawa's film portrayed a nation renewed after a great post-war recovery.

The 1964 Olympics film Tokyo Olympiad was directed by Kon Ichikawa – a key figure of Japan's "Golden Age" of cinema (Credit: Courtesy of the Criterion Collection)

By the time Japan surrendered to the Allied Forces on 15 August 1945, the country had suffered around 2.8 million casualties, lost up to 25% of its national wealth, and was left with 13.1 million unemployed. "People who lived in Japan through the war lived through a very difficult and challenging period," says Dr Alexander Jacoby, Senior Lecturer in Japanese Studies at Oxford Brookes University.

But the years that followed were marked by significant agricultural and industrial reforms, as new trade union laws provided opportunity for income growth, and US occupation led to a concerted effort to reintegrate the country as a global economy (and by 1968, Japan was the second-largest economy on the planet). "They'd been decisively defeated, and suddenly everything changed," Jacoby continues. "And cinema in the 1950s was really engaged with that transformation. It was a very fertile time for the arts."

When in 1959 prime minister Nobusuke Kishi won the bid for the 1964 Olympic Games, he secured with it an opportunity to present a new, non-militaristic image of Japan on the world's stage. And the country's booming cinema would be the vital tool for amplifying that projection. Japan was at one of the peaks of its cinematic productivity, says Jacoby, with around 500 films produced in 1959. They were successful at home – and many were appreciated abroad, too.

A new vision of Japan

In 1951, Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon won Japan the Golden Lion at Venice for the first time in its history; Ishirō Honda's 1954 nuclear monster movie Godzilla, meanwhile, was re-edited for a US audience just two years after its native release, to the tune of $2 million in box office receipts (around $19.5 million in 2021). And in terms of both his reputation and philosophy, director Kon Ichikawa – "widely shown and discussed in the West" says Jacoby, after his 1956 pacifist classic and Academy Award-nominee The Burmese Harp, and horrific 1959 anti-war statement Fires on the Plain – was the perfect candidate to deliver a cathartic statement for the rejuvenated nation.

What Ichikawa ended up delivering wasn't just a great piece of propaganda; it was one of the greatest sporting movies of all time. A time-bending tapestry of exquisite cinematography and pioneering technological achievement, Tokyo Olympiad offered a greater depth and emotion than Romolo Marcellini’s La grande olimpiade (1961), and something far more compelling than Bud Greenspan's four-hour record of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, 16 Days of Glory (1986). Here was a singularly astute, and fascinatingly rich film: a deeply humanistic and artistic portrayal of events that captured a new vision of Japan and its people.

Ichikawa's documentary is considered to be one of the greatest sporting films of all time (Credit: Courtesy of the Criterion Collection)

The Japanese Olympic Committee were not entirely impressed, however, demanding it be edited down to 93 minutes from its lavish 168-minute run-time. This, after all, was a film that already paid little attention to the Japanese athletes (who won 29 medals in total that year, including 16 gold medals – the third highest behind the US and the USSR), and eschewed the traditional recording of results in favour of a stylised interpretation of each event.

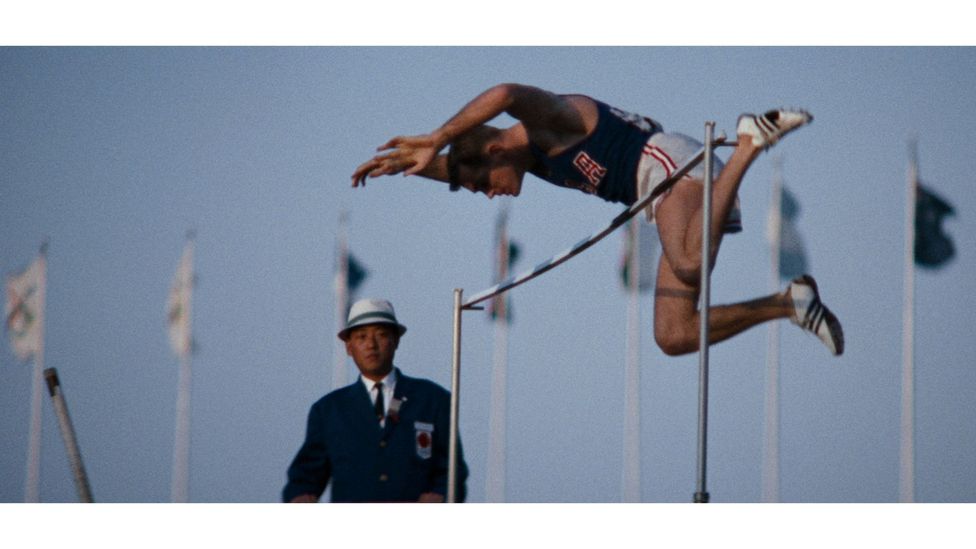

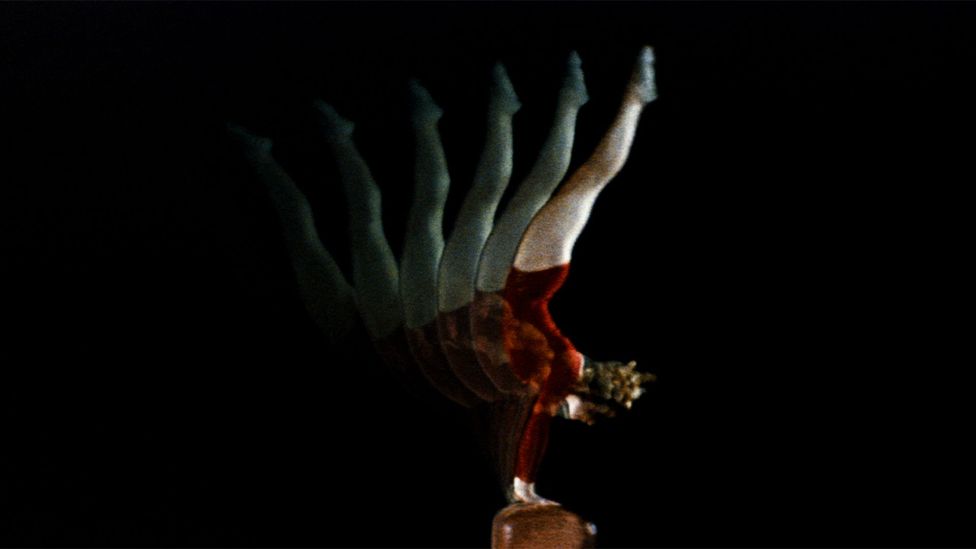

"Ichikawa was a fiction filmmaker," explains Jacoby. Tokyo Olympiad, then, was a fiction filmmaker's documentary. Cinematic and spellbindingly artistic, it is the Koyaanisqatsi of Olympics movies – an exercise of pure, hypnotic splendour. Observe the sumptuous blue that fills the screen during an aerial shot of the Olympic pool, or the monochrome freeze-frame as a team of men's sprinters cross the finish line; the magic of judo, volleyball and gymnastics, meanwhile, are shown using jump cuts, slow-motion and extreme close-ups. The film's most impressive shot sees an Olympic torch runner dwarfed by the colossus of Mount Fuji – the earthly wonder captured in all its awesome glory in a once-in-a-lifetime wide-angle shot ahead of the opening ceremony.

Such images were the product of hundreds of advanced cameras and state-of-the-art telephoto lenses – a far more lyrical embodiment of Japan's newfound technological advancement than the Shinkansen bullet train, which had been rushed to completion days before the Games despite having little to do with the event itself. The use of cutting-edge filming techniques, of course, had been a hallmark of Leni Riefenstahl's ground-breaking 1938 film Olympia, from the 1936 Games in Nazi Germany. But while she chose to glorify the physical bodies of Aryan athletes, explicitly mirroring them with images of ancient statues depicting the Greek Gods, Ichikawa instead sought to break new boundaries for spectators hoping to understand the psyches of the athletes in competition.

Tokyo Olympiad, with its use of cutting-edge techniques, was a lyrical embodiment of Japan's technological advancement (Credit: Courtesy of the Criterion Collection)

The silent, close-up, slow-motion camerawork used to capture the tension on the faces of competitors in the men's 100m sprint offers a prime example of Ichikawa's compelling and personal filmmaking style. So influential was this sequence that Ichikawa was later called upon by the International Olympics Committee in 1972 to be one of eight directors involved in the Munich Games film Visions of Eight (1973), where he transformed the 100m dash, once again, into a drawn-out examination of physical and mental torture. His methods have since been emulated countless times in sporting media: from the emotionally charged, slo-mo races in 1981 British sports film Chariots of Fire, to the close-up camera fixation on Bukayo Saka's face during the Euro 2020 final penalty shootout against Italy (and the subsequent devastation after he missed the decisive penalty to confirm England's fate as runners up).

A human endeavour

"Ichikawa described himself as a humanist," says Jacoby, and it is the director's empathy for his subjects that makes the film so magnetic. Shots linger on the beaten as much as they do the victorious: a lone, last-placed runner from Ceylon [modern-day Sri-Lanka] crosses the finish line alone to thunderous applause, in a scene that contrasts perfectly with the world-record-beating victory of Ethiopian marathon runner Abebe Bikila, who finishes having broken free from the pack in the film's climax. We see the injured being hauled off on stretchers; the grimace of a fallen cyclist; the exhaustion of a surrendering drop-out (the subtle parallels with wartime footage are not lost on Ichikawa). And on the podiums, a repeated shot contrasts the myriad of emotions on the faces of medal-winners: from ambivalence to awkwardness to tearful elation. It's a far more evocative and emotional presentation than we'd expect from a sporting competition otherwise so obsessed with neatly ranked places and pinpoint decimals.

Ichikawa was prone to ignoring the action altogether. He notably prioritised the children waving flags beyond a blur of racing athletes in one cycling event. But in choosing to capture the awe on the faces of the Japanese public – using handheld cameras that mimicked their gaze – Ichikawa made the collective people a far stronger national presence than any one individual Japanese competitor. Their anticipation and elation embodied the peaceful, human image of the nation far more effectively than the performance of any strongman, judo fighter or supple gymnast could. These audience shots would be something of a modern trait, too – perhaps we can thank Ichikawa for so many images of strawberry-munching spectators during the annual Wimbledon tennis tournament coverage.

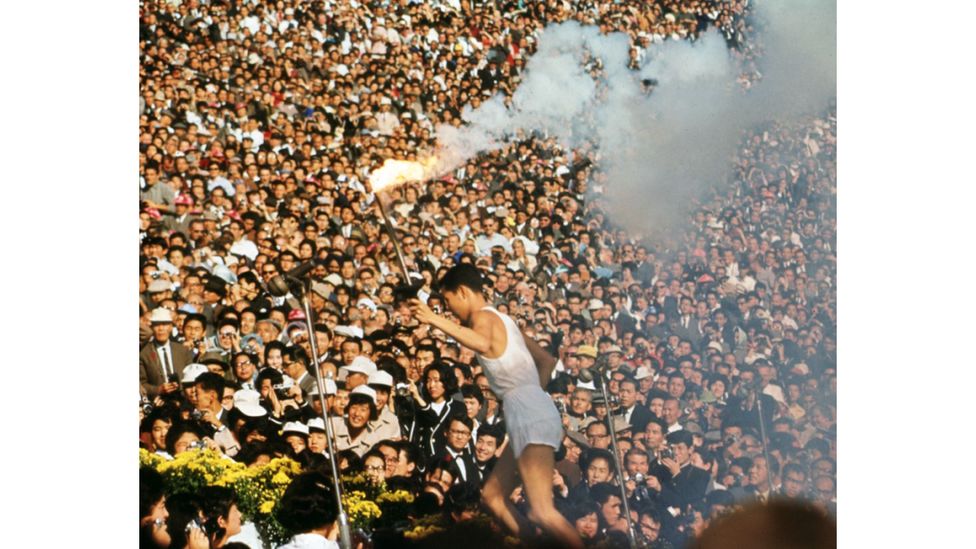

And while Tokyo Olympiad does constantly remind the viewer of the war that had divided the competing nations just 19 years prior, such scenes are presented poignantly. In a clear juxtaposition to Riefenstahl's Olympia, which had opened with shots of the ruinous Acropolis of Athens in reference to the birthplace of the modern Olympic Games, Ichikawa's film appears to begin in the midst of an apocalypse. Opening scenes depict buildings demolished to make way for new Games arenas, with the concrete rubble recalling the bombed-out husks of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But after a visual of the Genbaku Dome (Hiroshima's Peace Memorial), we also see a cauldron burst into lively flames at the National Stadium before a cast of competing nations. The torchbearer was Yoshinori Sakai – born in Hiroshima the day the bomb fell on 6 August 1945.

This was a statement that summed up Japan's great reintegration into the world, laid out in the opening titles: "The Olympics, a symbol of human endeavour". It is followed by the symbolic image of a great white orb hanging in the sky, channelling at once the Olympic rings, the Japanese flag, and a bright new dawn for the nation. At the Venice Film Festival, the jury had praised Burmese Harp for portraying "men's capacity to live with one another." Here, Ichikawa asked in the film's closing statement, "Humans share a dream every four years. Is it enough for this peace to be merely a dream?".

The 1964 Olympics' torchbearer was Yoshinori Sakai, who was born in Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 – the day the atomic bomb fell (Credit: Courtesy of the Criterion Collection)

So much time has passed since the last Tokyo Olympics that many of the countries that competed in 1964 no longer even exist. And yet the Games has been a mainstay, continuing without fail every four years since the post-war restart in 1948. The Covid-19 pandemic caused the first major delay in the Games since World War Two. This year's event is going ahead, despite the fact that international fans will not be permitted to travel to the country to attend and no spectators will be allowed in Tokyo at all. Some wonder if it's worth it – the majority of the public in Japan still want the 2020 event to be postponed, or abandoned altogether – but the situation is not so simple.

The past decade has seen a Japan still reeling from the bursting of the bubble economy in 1990 (the "lost decade" of the 90s is now referred to as the "lost thirty years") subjected to further devastation. The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami (which caused the accident at Fukushima) was the costliest natural disaster in history, with estimated damages of up to 25 trillion yen (£189bn). The 2020 Olympics, decided by a winning bid in September 2013, has thus come to be labelled by the press as both the "Reconstruction Olympics", and now the "Recovery Olympics", in an effort to champion the country's resilience and hard-fought restoration. But if the Recovery Olympics fails, it would be a PR and economic disaster.

'Showing both sides'

So, the Games are going ahead – which means Naomi Kawase's film will, too. And with the official film in the hands of a highly skilled and internationally renowned filmmaker regarded for her own empathetic portrayals of the country and its people, the Olympic Committee might feel confident of a successful national re-branding, much like the one they achieved in 1964.

Kawase is already a symbol of the country's restored cinematic prowess: in the two-and-a-half decades since her historic 1997 feature debut Suzaku, film production has exploded in Japan – while her own works have become a staple at leading international film festivals. A wealth of talented female filmmakers – including Miwa Nishikawa (Dear Doctor, 2009), Momoko Andô (Kakera: A Piece of Our Life, 2009) and Naoko Ogigami (Close-Knit, awarded the Berlin Special Jury Prize in 2017) – have also risen to prominence in the wake of her success.

The director's transition from "personal, documentary-style [films that] opened the eyes of the Western people" to "major feature films" (such as 2020's multifaceted exploration of motherhood, True Mothers – Japan’s official submission to the 2021 Academy Awards) is evidence of her growing precedence as a filmmaker, says The Japan Foundation's Senior Arts Programme Officer Junko Takekawa. Dr Jacoby points out, meanwhile, that when Kawase moved into feature filmmaking, she retained the compassionate and stylistic merit that had launched her to international recognition: "she herself said that she approached fiction with a documentarian's gaze."

The ability to empathise and amplify her subject matter will be vital for Kawase's 2021 Olympics film. But the director's statement, summarised in a 2012 Tedx Talk, perhaps underlines the significance of her role this year even further: movies, she believes, "can become a bridge for connecting people."

With her 1997 debut, Suzaku, Naomi Kawase became the youngest – and first female – recipient of Cannes' Camera d'Or prize (Credit: Bitters End)

The unique circumstances of the 2020 Games may, in fact, transform the lens through which Kawase captures the events altogether. Because Covid-19 means that audience numbers are restricted, "she may actually take it as a kind of record of what happened in 2021," says Takekawa. "[And] it might not even have that personal touch [for which she is usually known]."

Kawase agrees with this sentiment. "This is an unprecedented time within history," she tells BBC Culture. "It's Japan's responsibility to make this Olympics work and to take these measures against what’s happening in the world… and to reinterpret that idea of the essence and ethos and spirit with which the Olympics began."

The torch relay has already passed through Fukushima; the television footage received praise and criticism for highlighting the recovery of the areas over those corners still reeling from the destruction. But, "the Olympics refocuses what happened in Fukushima or Tōhoku," says Kawase. "Maybe at least [it can] make people rethink about what happened."

Either way, these diverse perspectives are ultimately at the heart of what Kawase wants to capture in 2021: "I don’t just want to convey the beauty of the Olympics or the athletes. I want to see it from right in the middle as a spectator and see it objectively, more than subjectively. To show both sides of the event is my mission… both the beauty and the catastrophic side of Japan together."

It's a philosophy that seems to echo that of Ichikawa's film. And while Kawase relays admiration for Tokyo Olympiad, she also cites a crucial difference in approach. "[Tokyo Olympiad] is not just a documentary. There is a taste of fiction imbued in the film as well," she says, pointing to the deep stylistic traits Ichikawa enveloped into his film. The importance of an objective stance is, to Kawase, of greater significance in capturing an event taking place during such an unprecedented time. "I hope I can show what happened this year in Japan to people in 100 years' time", she says. "[Because] I really want to show how the pandemic changed the world."

Tokyo Olympiad is available to stream on the Criterion Collection.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"film" - Google News

July 23, 2021 at 06:03AM

https://ift.tt/3Bp1YAS

Tokyo Olympiad: The greatest film about sport ever made - BBC News

"film" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2qM7hdT

https://ift.tt/3fb7bBl

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Tokyo Olympiad: The greatest film about sport ever made - BBC News"

Post a Comment