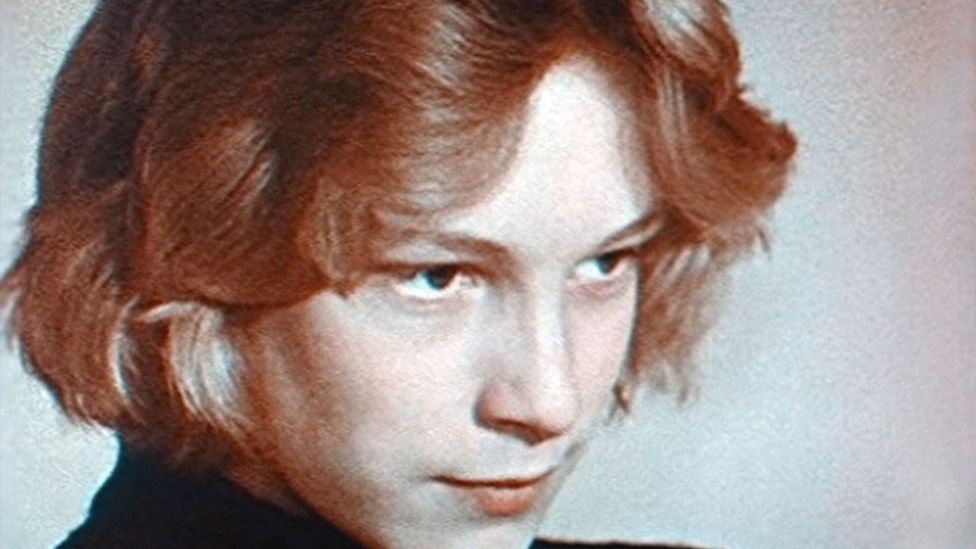

Fifty years ago, the revered Italian director Luchino Visconti searched far and wide for a young boy to star as the embodiment of youthful beauty in his film adaptation of Thomas Mann's novel, Death in Venice. The character, Tadzio, is the object of obsession for ageing composer Gustav von Aschenbach (played by a 50-year-old Dirk Bogarde). The child actor that impressed Visconti enough to play him – a character whose "face recalled the noblest moment of Greek sculpture", in the words of Mann – was 15-year-old Swede, Björn Andrésen.

More like this:

– The dark history of kids' animations

– What makes a Hollywood power couple

– Is the age of the celebrity over?

However, while working with one of European cinema's great directors when still a teenager may sound like a dream opportunity, it was anything but. A new documentary, The Most Beautiful Boy in the World, tells the story of Andrésen in the aftermath of landing the role, exposing the inadequate care afforded to him on set and looking at how he then emerged into a queasy limelight as the child object of grown-up desire. The film also tells of the tragedies that befell Andrésen before and after Death in Venice spun his life off its axis. The Andrésen we meet today is haunted by experiences depicted in the documentary – and, it is clear that if Death of Venice isn't the source of all his pain, then it has certainly contributed a lot of it.

Björn Andrésen was chosen to play the embodiment of youthful beauty in Death in Venice – and faced exploitation as a result (Credit: Alamy)

Footage of the casting process shows a leery Visconti asking the teenager to strip down to tiny pants, and commenting on his beauty in Italian, knowing full well that the child cannot understand. This grim objectification would be a motif of their relationship. The title of the film comes from a tag that Visconti gave the boy at the film's world premiere in London. However, two months later, at the 25th edition of the Cannes film festival, with the uncomprehending Andrésen sat beside him at a press conference, he would talk about their first meeting saying "He was even more beautiful back then. He has aged now — you can see he’s at an awkward age".

A troubled lineage

Andrésen, of course, wasn't the first or the last child for whom stardom was a very poisoned chalice. From Judy Garland to, most recently, Alan Kim, the young star of Oscar-winner Minari, the industry loves to coo over precocious kids, but who is looking after them once the cameras stop rolling? Who is making sure they have the tools to navigate the spotlight with their mental health intact? In the case of Garland, it is now a matter of infamy that she was given barbiturates and amphetamines by the studio in order to curb her appetite and keep her energy levels up, which led to a lifelong addiction, a story told in the 2019 biopic Judy. It's common for child actors to become wayward in teenhood, the age-appropriate desire to rebel given rocket fuel by fame and fortune. Or the problems can start even earlier: after shooting to fame aged 7 in ET, Drew Barrymore had an alcohol addiction by 11, and a drug addiction to 12, but went to rehab and survived. However, Brad Renfro, young star of The Client (1994) among other films, wasn't so lucky; after years of substance abuse and brushes with the law, he died in 2008, aged 25, of a heroin overdose. Meanwhile the likes of Dakota Fanning, Kirsten Dunst, Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson seem to have navigated the transition to adult stardom intact, although we can never know the psychological fallout happening behind closed doors.

Certainly, though, there are some child actors who look back on their experience with relative serenity. "I cried," says the now 22-year-old Jared Gilman on his reaction to finding out that he had been cast as one of two leads in Wes Anderson's 2012 film Moonrise Kingdom about a pair of 12-year-olds, Sam and Suzy, who run away to get married. "It was only the second time in my whole life that I ever cried out of happiness. The first time was when I won a TV at a raffle."

Shooting took place over two months in Rhode Island from April to June 2011 and Gilman has only exultant memories of this time. "I still consider it one of the best experiences I’ve ever had." He and his young co-lead Kara Hayward spent weekends ahead of the shoot at the production’s basecamp rehearsing and, in Gilman's case, learning how to kayak and cook a fish over an open fire – skills needed when the two go on the run in the great outdoors. Loyal to Anderson to this day, Gilman credits the director with easing the two of them into the shoot by scheduling it so that their scenes together came before they had to act opposite big adult stars, like Bruce Willis, Bill Murray, Ed Norton and Frances McDormand. By this point, they were comfortable.

Perhaps the most challenging scene they had to film was the one in which Sam and Suzy dance together in their underwear, kiss, and Sam is invited by Suzy to put a hand on her chest. "That was the last thing that we filmed. It was a closed set, and we rehearsed it beforehand," explains Gilman. But was it overwhelming to have that level of intimacy with a girl in front of the camera at an age when he wasn't even yet a teenager? Gilman explains he had been movie-obsessed since the age of five and had a professional detachment, even at 12. "I was aware that I was playing a character in a movie. As an actor, you might turn to your memories or feelings but ultimately you know it's for the job."

As a young star, Judy Garland was given barbiturates and amphetamines to curb her appetite and keep her energy levels up (Credit: Alamy)

In terms of the duty of care afforded him, Gilman had a chaperone in the form of his mother and received on-set tutoring together with Kara and the child actors who play a troop of scouts. Work days, incorporating three to five hours of schooling, totalled eight to 10 hours, as per Gilman's recollection. ("I am not an objective resource!", he cautions.) What he does know for certain, however, is that, "I enjoyed every day I worked on set, so I was totally OK with it, but we were working long hours," he says. "I was not upset about that at all. It's just the nature of how things are, especially if you're in a Wes Anderson movie, it's hard to get everything done in nine hours. We were never working crazy hours, it was just maybe an extra hour or two [than a standard working day]."

How child stars are protected – or not

In the United States, the activities of child actors are regulated by state laws, meaning that working conditions are more variable – and often more lax – than in the UK, where there is nationwide legislation and an organisation set up to monitor industry practices, the National Network for Children in Entertainment and Employment (NNCEE), which exerts a considerable and growing influence over productions up and down the country.

Ed Magee is the current chairman of the advisory group founded in 1994. "We're an organisation that helps improve practice, and safeguards children, but also makes sure that people are complying with the regulations and that they understand them. As an organisation, we spend a lot of time discussing what the legislation [around working conditions for child actors] actually means. Because, like any legislation, it can be open to interpretation. And sometimes you do have to say to people, 'Well, actually, you know, that's not quite what it says.' So it's about holding people accountable and making sure that children, when they are working, are safe and protected at all times."

The main piece of legislation in England is The Children (Performances & Activities) Regulations 2014, bolstered by The Children and Young Persons Act 1963, which stipulates that from birth to the end of statutory schooling at 16 (the last Friday of June in Year 11) an actor requires a performance license approved by the local authority for each production they work on. The decision to grant a license is based on whether the education, health, safety and wellbeing of the child will be maintained. Hours are carefully set with 9.5 hours being the maximum that a child actor can spend at a rehearsal or performance venue, a figure that includes work, schooling and mandatory breaks.

One crucial thing that the NNCEE does is to train child chaperones who accompany the child on set to make sure that the conditions of the performance licence are being upheld, from keeping a tally of hours worked to the more ineffable matter of ensuring that a child is safe. Magee delivers training to chaperones once a month with the goal of instilling in them the confidence to raise safeguarding concerns as they arise. He believes it is better for families of child actors to employ professional chaperones, or teachers, rather than to have family members stepping in. "It's very rare for parents to tell us when things go wrong, because parents are very worried that if they do, their child may not perform in the future. It's a very small industry."

This speaks to one of the saddest elements of The Most Beautiful Boy in the World: the role of Andrésen's grandmother, who was also his guardian and by his account, pushed him into the spotlight, too blinded by the prospect of fame and fortune to contemplate the wellbeing of her young charge. "[Granny] put my name down for all sorts of things. I don't know, I suppose I just went along with it. She wanted a celebrity for a grandchild," he says, early on, in his narration. This version of events is reinforced later in the documentary by a childhood friend who comments on the contrast between his grandmother's excitement and Andrésen's lack of excitement at his sudden stardom. His abiding interest was playing the piano and making music, something he perseveres with to this day.

Now 22, Jared Gilman looks back fondly on his time playing one of the 12-year-old co-leads in Wes Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom (Credit: Alamy)

Magee concedes that more parents, as well as more chaperones, are reaching out to the NNCEE as they circulate their messaging and make reporting concerns easier. His immediate goal is to create a button – like the one on the Child Exploitation and Online Protection site – that enables a report of mistreatment to be delivered to the relevant authority in one click of the mouse.

Even so, he holds firm to his belief that a professional chaperone is the safest option. "They should be employed on a production because they know what they're doing. They actually know the legislation. They've been trained to look at safeguarding issues. We go through some very practical things in our training sessions about what to do if, for example, you find somebody in a toilet that was marked very clearly for a child."

Child stars in adult worlds

Above and beyond how child actors are treated on set, the nature of the role they are being asked to play can also have an impact on their experience. There is a real, qualitative distinction to be made, for example, between the type of roles that the cast of Harry Potter played (fantastical parts involving magic powers on a child-dominated set) and the one that Andrésen did. In the mildest interpretation, his character Tadzio was a catalyst for ragged adult devastation and, in the starkest one, the object of a paedophile's gaze. The documentary chronicles how that latter gaze followed him out of the boundaries of the film and into his real life. Andrésen recounts in The Most Beautiful Boy in the World that during filming, Visconti had warned the crew that he was sexually off limits – but this protection ended once the film was wrapped, when in Andrésen's words, he had "served [Visconti's] purpose". After the Cannes premiere, he was taken to a gay club by Visconti while very drunk, an experience he describes in the film as "hell". Later. he accepted the opportunity that his unique type of celebrity had opened up: the patronage of older men. The exact nature of his relationship with them is left ambiguous in the documentary, but he travelled the world on their coin, a choice he bitterly regrets.

Casting children in brutal or sexual films that they would be prohibited by age restrictions from seeing is a quandary that the industry has yet to reckon with, despite the troubling testimonies out there. Natalie Portman, whose break-out role came aged 13 when she played the unlikely best friend to a hitman played by Jean Reno in Léon (1994), recalled the consequences of taking that part when speaking at a LA Women's March in 2018: "I excitedly opened my first fan mail to read a rape fantasy that a man had written me. A countdown was started on my local radio show to my 18th birthday, euphemistically the date that I would be legal to sleep with." Meanwhile the same year, Kirsten Dunst, aged 11, starred as the young vampire, Claudia, opposite Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise in Interview with the Vampire, a role that required her to kiss Pitt, then 30. Doing press at the time she said that she hated doing the scene "because Brad was like my older brother on set and it’s kind of like kissing your brother. It's weird because he's an older guy and I had to kiss him on the lips, so it was gross."

Gilman's character on Moonrise Kingdom exists in a space between child and adult worlds. Sam is precocious, as a misunderstood orphan who decides to marry his first crush, and intertwined around Sam and Suzy are adult storylines that, as is often the case in Anderson pictures, involve melancholy and depression. However Gilman says that he didn't realise what the adult characters were going through until he watched the film, as during the shoot he was focused on his own character.

Many of the biggest challenges of being a child actor don’t drop into place until the film's release. "Our advice [to productions] is always, 'How are you going to make sure the child stays supported, not only by filming it, but also when it's broadcast?'" says Magee, "Because I think that's a different issue. A child can feel very well supported by the filming but when they walk into the playground and other people are seeing it, then that's where the duty of care kicks in as well."

Natalie Portman has spoken out about the 'sexual terrorism' she suffered after her breakout role aged 13 in 1994 film Léon (Credit: Alamy)

The consequences for Gilman, who was in seventh grade when the film came out, is that he was known for Moonrise Kingdom "in a pretty sustained way" and was asked to give a talk in front of the whole school about the experience of making it. "Throughout my school years, maybe more so the year after the movie came out, my friends were telling me how awkward they felt watching the beach scene. I get it. I'm their friend and they're seeing me dancing shirtless and then doing what I did [putting his hand on Suzy’s chest]. I also understand that with regards to other child actor experiences that you hear about, I was pretty unscathed."

The pressures – and fickleness – of fame

It's worth noting, however, that Gilman may have experienced a more amenable type of child stardom, with his role in a highbrow, critically-admired arthouse film, than those child actors who have to deal with the full brunt of the Hollywood machine via very commercial films in which they may be a kind of brand – think, in the past, of Lindsay Lohan and Macauley Culkin and all the Disney-affiliated child stars of this world, who have achieved a celebrity platform that has seemed to make them fair game for taking down a peg or two by the less scrupulous side of the press.

Then there is the fickleness of the industry to contend with, which is difficult for actors at any age, let alone those just going through puberty. After Moonrise Kingdom, Gilman went on to star in a few films, but none of them were hits. For all the good memories that Gilman has of making Moonrise Kingdom, achieving a plum role with a renowned director at such a young age has led to him forging a wistful attachment to an ever-receding period in time (What a striking coincidence that nostalgia is a motif of Wes's worldbuilding). Of the Moonrise Kingdom cast and crew, he says: "I miss the hell out of them and I want to go back. It's like going to the Chocolate Factory, and then walking out without the keys."

Gilman is philosophical about the anxiety that followed as he grew up and continued to pursue acting under the long shadow of Moonrise Kingdom, navigating bad luck and bad timing as projects fell through at various stages. He is candid about the struggles he had as a teenager while at pains to avoid blaming anyone on the production. "I definitely did have a brain that was very self-critical. I did have a lot of anxiety, but I've been that way, really since before? I was treated very well and if I had issues, it's nothing to do with anyone on the Moonrise set." Now 22 and a student at NYU, he plans on taking a leave of absence in order to focus again on his number one love: acting.

I put it to both Gilman and Magee that the duty of care for child actors should involve ongoing mental health support. Magee says that this is covered implicitly in the existing UK legislation by the imperative to look after a child’s "wellbeing" – although the terms of what that support should entail could be made clearer. He believes that productions of all sizes should "have a psychologist or a psychiatrist or a counsellor who can talk to the child, not only while filming, but also afterwards". Gilman takes a shine to the idea, which hadn't crossed his mind before. "Just to process the whole thing and reintegrate into reality? That might not be a bad idea – I mean, for everyone on the shoot!"

One detail that comes across in The Most Beautiful Boy in the World is that no one cared to listen to Andrésen. Collaborators and admirers alike were so dazzled by his looks that they were content to bask in their glow; all the while he mentally flailed in secret. For child actors to stand a chance of making it to adulthood without major damage, it's vital that there are people in their lives, and on the production, who don't care about the superficial trappings of fame so much as they do the child actor's interests and wellbeing – and, beyond that, that our wider culture's attitude to child stars is to treat them not as "famous people" but the vulnerable beings they are. Celebrity worship is a social epidemic, and it's on all of us to look in the mirror and see what – and who – we're missing by participating in this most craven of churches.

The Most Beautiful Boy in the World is released in the UK and Australia on 30 July and the US on 24 September

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"film" - Google News

July 22, 2021 at 02:00PM

https://ift.tt/2WblD7c

Death in Venice and how film has mistreated child stars - BBC News

"film" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2qM7hdT

https://ift.tt/3fb7bBl

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Death in Venice and how film has mistreated child stars - BBC News"

Post a Comment